Core 1 graphs: all you need to know

Part I: Basic shapes of Core 1 graphs

There are a handful of basic shapes of graphs you need to know about for C1, namely:

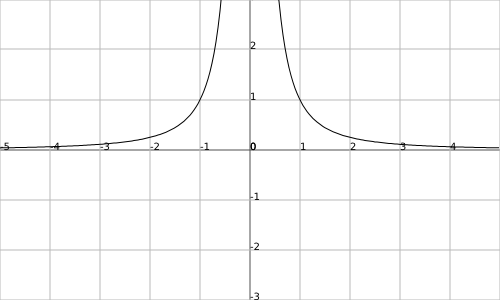

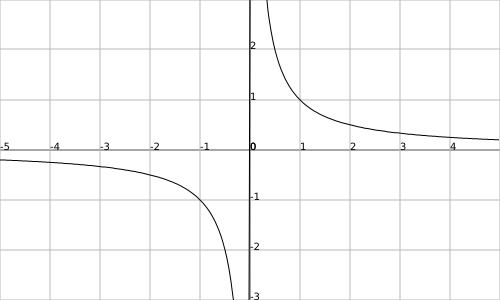

- reciprocal graphs ($y = frac{1}{x}$)

- reciprocal-square graphs ($y = frac{1}{x^2}$)

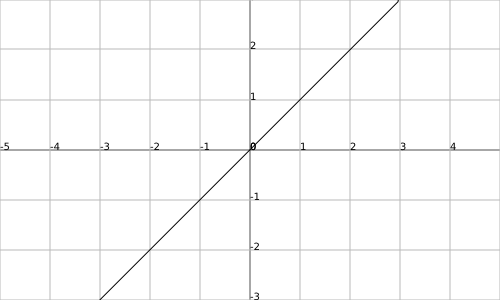

- straight line graphs ($y = x$) - you know this one, right?

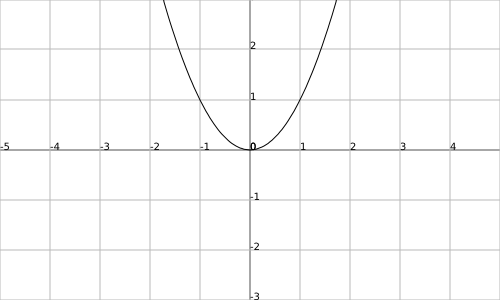

- quadratic graphs ($y = x^2$)

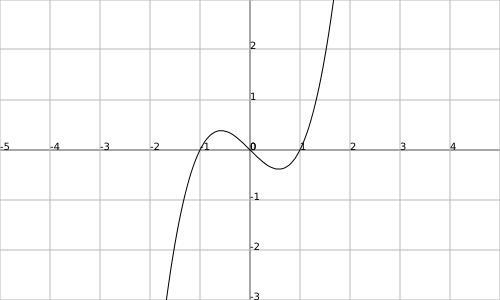

- cubic graphs ($y = x^3 - x$, for this one)

There are other possible cubic graphs, but you’re not going to see them in C1.

Of course, all of these graphs can be moved and stretched in many ways. To see how, read on!

Part II: Transforming graphs

Let me introduce you to bad guy $x$ and good guy $y$.

Bad guy $x$ is a very bad guy - he’s in bracket-prison because he always does the opposite of what he’s told. If you replace an $x$ with $(2x)$, for instance, you’re telling bad guy $x$ to stretch out twice as wide but he says ‘no! I’m bad guy $x$, and I do the opposite of what I’m told!’ and becomes half as wide instead. If you replace an $x$ with $(x - 2)$, you’re telling him to move two to the left, but he moves two to the right instead.

The only thing bad guy $x$ does right when you tell him is turn around - if you replace an $x$ with $(-x)$, the graph flips sideways.

Good guy $y$ on the other hand, is an upstanding citizen and lives outside of bracket prison. If you put a $+ 2$ outside of brackets, telling good guy $y$ to go jump, he says ‘how high? oh, two!’ and he moves up two. If you multiply by four, good guy $y$ stretches the graph vertically by a scale factor of four.

And if you put a minus in front, it flips upside down. All very easy!

Part III: crossing the axes

This is probably the hardest bit of sketching graphs, so pay attention!

The easiest way to think about where a graph crosses axes is to think about the co-ordinates of the points where it does it. You might not know exactly where a graph crosses the $y$-axis, but you know its co-ordinates are (0, something) - that is to say, $x = 0$. What you do then is replace all of the $x$s in the equation with 0 and see what comes out.

Crossing the $x$-axis is similar - you know the co-ordinates are (something, 0), so $y = 0$; the only trouble is, you could have several possible solutions here. So here’s what you do: first up, make the equation as simple as possible. If you can get it into a form where $x =$ (something with no $x$s in), congratulations, you’ve found the answer.

Otherwise, you’ll need to factorise and get everything in brackets. Here, the rule is:

- for every bracket you have, see what $x$ has to be to make it 0. (If you have $(x - 2)$, then $x$ must be 2. If you have $(4x - 3)$, then $x = frac{3}{4}$.) At each of these possible solutions, the curve gets involved with the $x$-axis.

I say ‘gets involved’ because it could either cross the axis or touch it. How do you tell which is which? Well, it’s to do with the power of the bracket. If the whole bracket has a squared outside it, the curve touches the axis there. If it doesn’t then it crosses. It’s that simple!

Any questions about that? Pop them in the comments below!